|

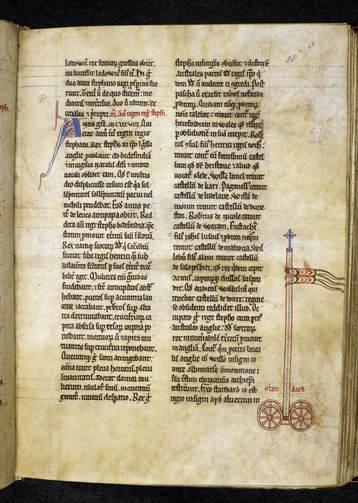

Ronald W. Braasch III Cellarer’s Chequer of Barnwell Priory. Accessed December 1, 2018. Photo by Keith Edkins, Geograph, https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/798404. Manuscripts (A) London, College of Arms, MS Arundel 10 (C) Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 175k (M) Oxford, Magdalen College, MS lat. 36 (V) London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius E. xiii (L) London, British Library, MS Add. 35, 168 Editions Stubbs, William, ed. Memoriale Fratris Walteri de Coventria. London: Longman and Co. et al., 1872-1873. [Latin; Stubbs provided the Barnwell text as a comparison to Walter of Coventry] Description The record of annals from the incarnation to 1232, known as the Barnwell Chronicle, occupies seventy-two folios in a single extant Manuscript, MS Arundel 10, located today in the London, College of Arms. It is particularly valued for its coverage from 1202-1225. After 1202, the entries become much more detailed, sometimes occupying several folios. It was composed within a generation of John's death. At the end of the thirteenth century, the manuscript made its way into the possession of the Barnwell Priory (above) but was probably not written there. It has been argued in recent years that the Barnwell Chronicle is not the progenitor of the Walter of Coventry manuscripts. Donald Kay has traced its creation from a manuscript of Roger of Crowland, a theory seconded by Cristian Ispir’s PhD dissertation in 2015. Importance to Angevin History The manuscript has been prized for its detailed and measured account of the last years of King John’s reign. It is useful not only as a general itinerary of John, but also the series of events leading up to the Magna Carta and the invasion of Louis (later Louis VIII of France). The chronicle ultimately considered John a tyrant, and the fall of Normandy inevitable. It is worth noting, however, that if one removed the name John –and all the connotations of his reign– from the text, the descriptions of a king besieging castles and wasting and destroying rebel lands through cruel and harsh warfare places John on an eerily similar footing to other rulers of the age. Bibliography

Hallam, Elizabeth, ed. The Plantagenet Chronicles. New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986. Ispir, Cristian. “A Critical Edition of the Crowland Chronicle.” PhD diss., King’s College, London, 2015. Kay, Richard. “Walter of Coventry and the Barnwell Chronicle.” Traditio 54, (1999): 141-167. Marvin, Julia. “Barnwell Chronicle.” In The Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Edited by Graeme Dunphy and Cristian Bratu. Last modified 2016. https://referenceworks.brillonline.com Morris, Marc. King John : Treachery and Tyranny in Medieval England : The Road to Magna Carta. New York: Pegasus Books, 2015. Seel, Garahm. King John an Underrated King. London: Anthem Press, 2012. British Library Royal MS 14.C.2, f. 88, image of a standard Manuscripts: William Stubbs lists ten manuscripts in his edition, but the ones of greatest significance are as follows: 1. British Library Royal MS 14.C.2 (covers up to 1180, believed to have been written in the twelfth century) 2. Bodleian Library Laud MS 5 8 (covers from 1181 to 1201, written in the early thirteenth century) 3. BL Arundel MS 69 (full account, written before 1213) See David Corner’s article from 1983 for a more recent treatment of the relationship and usage of these three MSS, which were A and B in Stubbs' edition. Editions "Rogerii de Hoveden annalium pars prior et posterior" in Rerum Anglicarum scriptores post Bedam praecipui (Frankfurt, 1601), 400-829. Chronica magistri Rogeri de Houedene, ed. William Stubbs, 4 vol., (London, 1868-1871). Translations Riley, H.T.. The Annals of Roger de Hoveden, 2 vol., (London, 1853). Description Finished in 1201, the Chronica, written by the ‘administrative historian’ Roger of Howden (sometimes Hoveden or Houeden), covers the years 732-1201 of English history. The Chronica is a massive undertaking of English historical compilation which William Stubbs, the text’s first and only modern editor, split into two divisions, in four volumes. The first part, which Roger based off the unpublished Historia post Bedam of Simeon of Durham and Henry of Huntingdon, picks up the history of England where Bede left off and continues up to 1148. The second, and arguably much more important contribution of Roger, records English history from the rise of King Henry II until Roger’s supposed death in 1201 early in the reign of John. Having accompanied Richard on the Third Crusade, Roger began writing his Chronica once he returned to England in 1192. A second major work written by Roger exists, though: the Gesta Henrici Secundi et Gesta Regis Ricardi, covering 1169-1192. This text was at first erroneously attributed to Benedict of Peterborough, though it is now known to have been written by Roger. The Gesta’s true significance has only more recently been discovered, though, by David Corner, who established convincingly that the Chronica is in fact, at least in part, a revision of the Gesta, and by John Gillingham, who concluded that the Gesta was, in a sense, Roger’s journal for the years 1169-1992, a “contemporary chronicle.” The Gesta Regis Ricardi, in particular, then provides an eyewitness record of the Third Crusade. The Chronica, as a revision of the Gesta, thus offers a well-written and researched history of England during the reign of Henry II and a thoroughly detailed and often personal account of the full reign of Richard I, highlighting the latter’s crusading. Importance for the Study of Angevin History The Chronica’s importance for the study of Angevin history is manifest. In it, Roger covers the beginning of Henry II’s reign and continues in great detail early into John’s. Roger, writing both in England and en route to / in the Holy Land, had to fill in the gaps left by his absences as best he could, so the parts that truly stand out are, naturally, the events for which he was present. For crusading history, as well as Angevin history, Roger is then an incredibly significant source. Additionally, as a formal royal clerk for Henry II (1174-1189), Roger’s writings provide a highly accurate image of the functions and processes in and around the Angevin court during the reigns of Henry and Richard. It is, however, Roger’s plainness and the straightforward nature of his style that makes him such an excellent source. He was not, as has been noted, writing solely as a “mouthpiece for the English kings,” (Staunton, 52) as many of his predecessors had done, and thus gives much insight into the more daily and regular happenings in the Angevin court. Roger, it seems, was primarily interested in being an historian, doing research, and recording the events to the best of his ability, though he was by no means perfect as becomes clear when he treats matters about which second-hand research was sparse or inaccurate. The sheer volume of writing that Roger produced, including full document citations and speeches, makes his Chronica a wealth of information of Angevin activities in the latter half of the twelfth century. Finally, comparing the Gesta and the Chronica offers an interesting glimpse into the process of writing history in late twelfth-century England. In this way, the Chronica shows how the past was glossed with present knowledge, such as of the failure of the Third Crusade, or even of the actions of Angevin kings (i.e. the Becket affair). Bibliography Barlow, Frank. “Roger of Howden.” English Historical Review 65 (1950): 352-360. Corner, David. “The Earliest Surviving Manuscripts of Roger of Howden's ‘Chronica’.” English Historical Review 98 (1983): 297-310. Gillingham, John. "Roger of Howden on Crusade", in Richard Cœur de Lion: Kingship, Chivalry and War in the Twelfth Century, 141-153. London: The Hambledon Press, 1994. Hughes, Paul. “Roger of Howden’s Sailing Directions for the English Coast.” Historical Research 85 (2012): 576-596. Staunton, Michael. “Roger of Howden: A Historian in Government,” in The Historians of Angevin England, 51-66. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017. Stenton, Doris M. "Roger of Howden and Benedict", English Historical Review 68 (1953): 574-582. Tanner Smoot Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 339, f.38r Description:

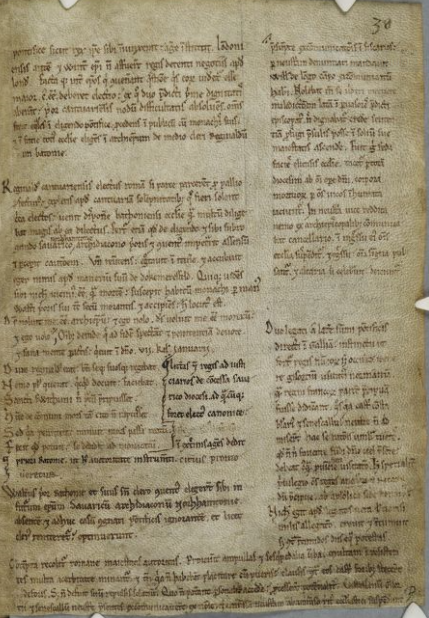

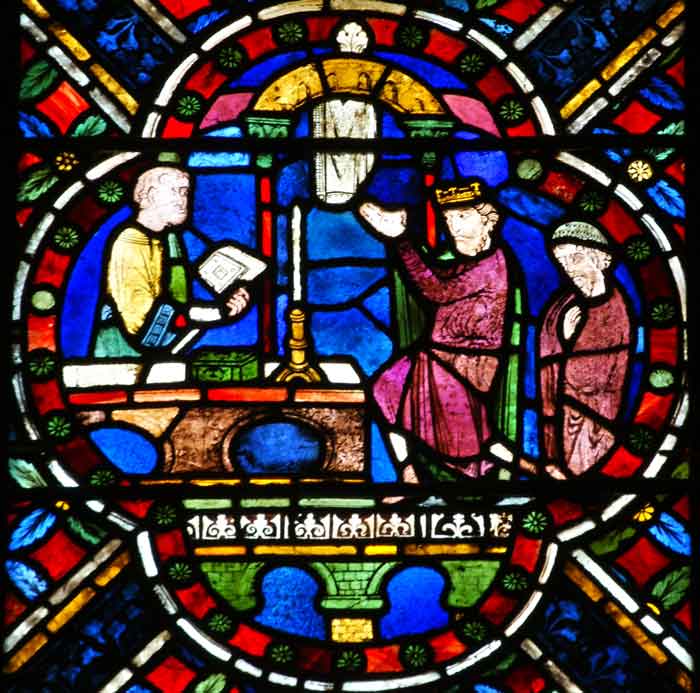

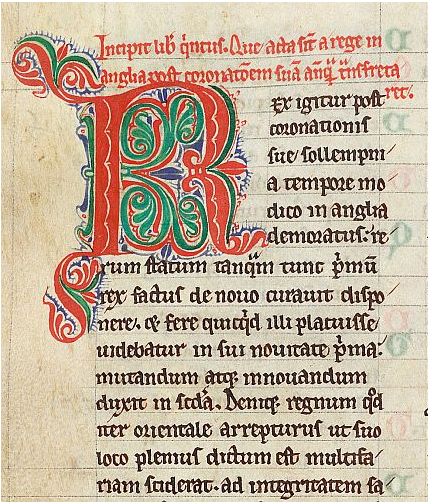

Completed some time between 1192 and 1198, the Cronicon of Richard of Devizes records contemporary events in England and Palestine from the coronation and subsequent departure of King Richard I from England for the Third Crusade until the king's decision to return from the Holy Land in 1192. Nearly everything known of Richard of Devizes' life comes from the small amount of autobiographical information supplied within the prologue of the Cronicon. Presumably from the town of Devizes thirty-five miles west of Winchester, Richard belonged to the Benedictine community of St. Swithun's connected to the Cathedral of Winchester. Richard states to have completed his chronicle at the request of his friend Robert, former prior of Swithun's and then Carthusian monk at Charterhouse. Only two manuscripts of Richard's Cronicon remain extant, and some scholars have postulated that these represent the only manuscripts of the work ever written. Richard maintains an extremely ironic tone throughout the entirety of his chronicle. While the content of the narrative appears almost entirely independent from any other contemporary historical sources, Richard's style displays a significant dependence on the satires of Roman authors such as Juvenal and Horace. In a manner similar to the ancient satirists Richard consistently exhibits a clever humor throughout his work, often mocking the political actors of his age, resenting zealous religious sentiments, and ridiculing local legends and folk lore. Many of the anecdotes present throughout the chronicle end abruptly and anticlimactically in a manner that mockingly undermines their seriousness. Richard appears to consciously disregard the traditional norms of twelfth-century historical writing, and refuses to moralize or exegize history despite his monastic background. The primary concern of Richard revolves around power and the unfettered ambition of the English aristocracy in the absence of Richard I. In this context, Richard frequently paints the English barons as puerile politicians committing virtual treason against the absent king. Richard's loyalty to Richard I corresponds to his general worldly conservatism and attachment to institutions, aristocratic values, and high culture. Importance for the Study of Angevin History: Richard's Cronicon offers an interesting and independent perspective on the political climate of late twelfth-century England which often eschews modern historians' expectations of how medieval individuals thought and wrote. While Richard presents a general and mostly unreliable account of the Third Crusade in his Cronicon, his connection to the important city of Winchester and his proximity to powerful authorities such as Bishop Geoffrey make his commentary on contemporary English history extremely valuable. As the Cronicon appears wholly original to Richard, the views expressed within its pages represent his independent observations of a pivotal time in English history. Yet, much remains uncertain about the purpose of Richard's chronicle, its intended audience, and the impetus of Richard's satire. Manuscripts: Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 339. British Library, MS Cotton Domitian A. XIII. Editions: Stevenson, Joseph. Cronicon Ricardi Divisensis de rebus gestis Ricardi primi Regis Angliae. English Historical Society: 1838. Howlett, Richard. Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, vol.3. London: Longman, 1886. Richard of Devizes. Chronicle. Translated by J. A. Giles. Cambridge, Ontario: In parentheses Publications: 2000. Richard of Devizes. The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes of the Time of King Richard the First. Edited by John Appleby. New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1963. Bibliography: Staunton, Michael. The Historians of Angevin England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. Appleby, John. Introduction to The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes of the Time of King Richard the First. By Richard of Devizes, edited by John Appleby. New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1963. Partner, Nancy. "Richard of Devizes: The Monk Who Forgot to be Medieval. In The Middle Ages in Texts and Texture: Reflections on Medieval Sources. Edited by Jason Glenn. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011. Further Reading: Gillingham, John. "Richard Devizes and 'a Rising Tide of Nonsense': How Cerdic met Arthur. In The Long Twelfth-Century View of the Anglo-Saxon Past. Edited by Martin Brett and David A. Woodman. New York: Routledge, 2016. King Henry II does penance at the tomb of St. Thomas Becket. Canterbury Cathedral By John Evans Description According Marcus Bull, were recorded by Benedict of Peterborough and William of Canterbury at Canterbury on the grounds of the shrine of St. Thomas, in front of the tomb or reliquary where Becket’s remains were preserved. The sex, appearance, place of origin, and social status of the pilgrims were recorded. Often they would answer a series of questions that would unravel the fullness of their stories. The miracles they encountered usually occurred elsewhere and the pilgrims would almost always end up as the stars of their own account. Unlike hagiography or historiography writing, miracle collections are not usually bound by chronology, but are usually thematically driven. Benedict’s miracle collection seems to have survived in more manuscripts, leading Bull to conclude it was the preferred version, whereas Staunton presents William’s miracle collection as the official version. We know that Benedict was more Biblical and localized in his scope whereas William could often be snobbish in his disdainful description of the poor. Book I of Williams’s writings was most likely presented to Henry II’s court. Relevance to Angevin History As Marcus Bull explains, William of Canterbury blatantly seems to reject Henry II’s invasion of Ireland as an unjust war throughout his collection stretching the norms even of the genre in which he is writing. However, if Bull is correct, Book I of the collection seems to present Henry II in a much more positive light, even depicting his victory over the rebellion of 1173/ 1174 as a direct response to a visit to the relics of the holy martyr. Nevertheless, on the whole William presents the royal figure in a negative light. Wielding a series of classical references and displaying a wide range of learning, William’s version of the Miracles is a clear indictment of Henry’s overreaching policies, in matters temporal and spiritual. Benedict, in my own opinion seems to do the same through the symbolism of the elder tree and Diocletian’s coin. This sentiment is seemingly supported indirectly by Bull when he explains why William’s text was sent to Henry rather than Benedicts. He makes the claim that Benedict had already a less than favorable relationship with the king. Whether this is true or not, it is clear that the miracle collections of Thomas Becket, by both William of Canterbury and Benedict of Peterborough depict struggles within the Angevin Empire between Henry’s attempts to maintain dominance over his vast empire and a clerical body seeking to critique these missuses of temporal authority. Yes, there were clerics on either side of the Becket affair, and yes there were even clergy who supported Henry’s invasion of Ireland. However the fact that Becket‘s oppositional stance was ultimately canonized coupled with the miracle collection’s concerns over due-reverence, lead me to identify William and Benedict’s authorial voice with clerical anxieties over royal power.

David Howes Editions:

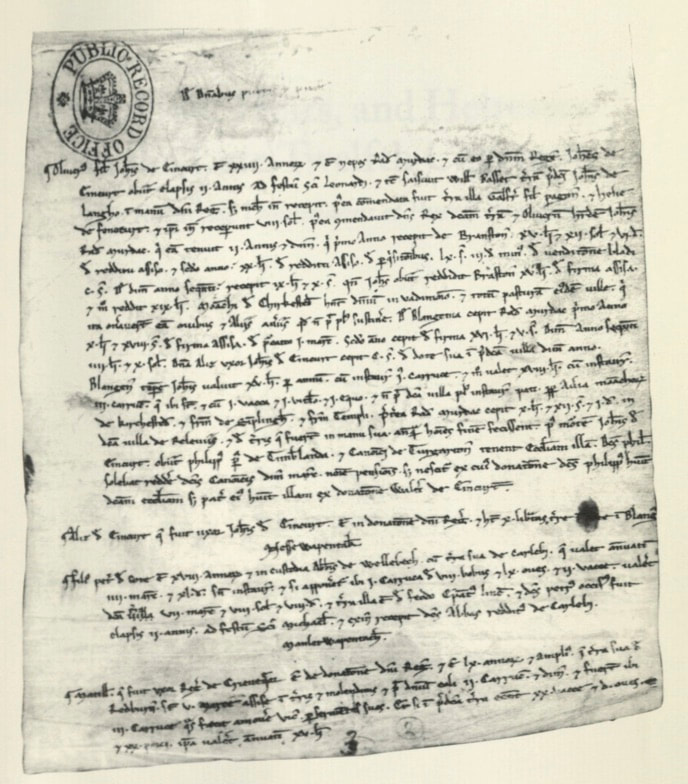

Grimaldi, Curante Stacy, ed. Rotuli de Dominabus et Ppueris et Puellis de Donatione Regis. London: William Pickering, 1830. Round, John H., ed. Rotuli de Dominabus et Pueris et Puellis. London: St. Catherine Press for the Pipe Roll Society, 1913. *Walmsley, John, ed., and trans. Widows, Heirs, and Heiresses in the Late Twelfth Century: The Rotuli de Dominabus et Pueris et Puellis. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2006. Manuscripts: (1643) British Library, Harleian MS 635, folios 148a-160a and 215b-217b *The National Archives, E198/1/2 Description: The Roll Concerning Ladies and Boys and Girls is a manuscript dated to 1184, and is a record of the values of properties owned by 128 widows and 96 heirs and heiresses. The Public Record Office preserved the Roll until 2003, when it was transferred to the National Archives in Kew, England. It is composed of twelve rolls stitched together along their edges forming more of a folding book. Each of the folios records the property of an individual within a county as stated in a hundred court, with the list subdivided by either hundred or, in the case of Lincolnshire, wapentake. In the roll, the counties are listed in the order: Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Rutland, Huntingdonshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Hertfordshire, Essex, Cambridgeshire, and Middlesex. Some counties have larger entries than others. For example, Lincolnshire has forty names with their corresponding properties, whereas, Huntingdonshire has only two. Further, the value of assets fluctuates as well. Some individuals are noted as holding only a couple shillings worth of property, while others had incomes of over forty pounds or more per annum. The handwriting is attributed to four clerks of the itinerate Justices: Hugh of Morwich, Ralph Murdac, Ralph Murdac, and Master Thomas of Hurstbourne. Importance for the Study of Angevin History Angevin historians can view the Rotuli de Dominabus et Pueris et Puellis as evidence for Henry II’s ambition of increasing royal revenue from royal and non-royal sources following the lacuna of chancery income during the period of Stephen’s reign. The Assize of Clarendon (1166) and the Assize of Northampton (1177) established the justices itinerate, and it is possible to view this Roll as the first enrolment of the justices’ visits. From Domesday to this Roll, there is no other comprehensive source available for familial revenues and landholding. Traditionally historians have used this source for understanding Angevin demographic, economic, historiography, and women’s history. Bibliography Introduction: Round, John H. “Introduction.” In Rotuli de Dominabus et Pueris et Puellis, xvii-xlvii. London: St. Catherine Press for the Pipe Roll Society, 1913. *Walmsley, John. “Introduction.” In Widows, Heirs, and Heiresses in the Late Twelfth Century: The Rotuli de Dominabus et Pueris et Puellis, edited and translated by John Walmsley, ix-xiv. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2006. Historiography: Amt, Emilie. The Accession of Henry II in England: Royal Government Restored, 1149-1159. Woodbridge; Rochester: Boydell Press, 1993. Lyon, Bryce. “ Part Three: Henry II and His Sons: The Angevin Sources.” In A Constitutional and Legal History of Medieval England, edited by Bryce Lyon, 217-243. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1960. Mortimer, Richard. “The King’s Government.” In Angevin England, 1154-1258. Oxford; Cambridge: Blackwell, 1994. Warren, W.L. Henry II. Berkeley; Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973. *----.The Governance of Norman and Angevin England 1086-1272. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Athenaeum Press, 1994 Demographic & Economic History: Moore, J.S. “The Anglo-Norman Family: Size and Structure.” Anglo-Norman Studies 14, (1992): 143-96. Hallam, H. E. “Farming Techniques: Eastern England.” In The Agrarian History of England and Wales, edited by J. Thirsk. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Herlihy, David. “The Transformations of the Central and Late Middle Ages.” In Medieval Households, 79-111. Cambridge; London: Harvard University Press, 1985. Moore, J.S. “The Anglo-Norman Family: Size and Structure.” Anglo-Norman Studies 14, (1992): 143-96. Women’s History: Amt, Emilie. Women’s Lives in Medieval Europe: A Sourcebook. London; New York: Routledge, 2010. Johns, Susan M. “Royal Inquests and the Power of Noblewomen: the Rotuli de Dominabus et Pueris et Puellis de XII Comitatibus of 1185.” In Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the Twelfth-Century Anglo-Norman Realm, 53-194. Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press, 2003. Hallam, H. E. “Farming Techniques: Eastern England.” In The Agrarian History of England and Wales, edited by J. Thirsk. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Patrick C. DeBrosse Avranches, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS. 159, f. 205r From Pohl, "Date and Context," p. 11. Manuscripts

Avranches, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 159. [Robert's working copy] While Robert's working copy of the Chronicle survives, the subsequent manuscript tradition is complicated by the fact that some copies seem to have been made at intermediate stages during Robert's composition. An overview of the 18 surviving "core" manuscripts and their relationship to one another is in Delisle, "Préface," liii-lv. Howlett, "Preface," pp. xxxvii-lxv, offers somewhat different conclusions about these same 18 manuscripts. Benjamin Pohl reevaluated and revised some of Delisle and Howlett's conclusions in Pohl, "Date and Context," 1-18. Modern Editions and Translations Robert of Torigni. Roberti de Monte Cronica. In G. H. Pertz (ed.), Monumenta Germaniae historica inde ab anno Christi quingentensimo usque ad annum millesimum et quingentesimum: Scriptorum; Tomus VI, edited by C. Berthmann, 475-535. Hanover: Impensis Bibliopolii, 1844. _____. Chronique de Robert de Torigni, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel. 2 volumes. Edited by Léopold Delisle. Rouen: A. Le Brumentm 1872-3. _____. Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II., and Richard I.: Vol. IV; The Chronicle of Robert of Torigni, Abbot of the Monastery of St. Michael-in-Peril-of-the-Sea. Edited by Richard Howlett. London: HMSO, 1889. _____. The Chronicles of Robert de Monte. In The Church Historians of England: vol. IV; Part II. Translated by Joseph Stevenson. London: Seeleys, 1856. [partial English translation]. Description Robert of Torigni, monk of Bec and subsequently (from 1154) abbot of Mont-Saint-Michel, was a prolific writer, whose first major project was a continuation of the Gesta Normannorum Ducum. Robert's Chronicle, was his ambitious follow-up: a world history, which sought to narrate events from the time of Abraham to Robert's own lifetime, with a particular emphasis on events within Normandy and England. Robert copied the bulk of the pre-1100 portion of his Chronicle from Sigebert of Gembloux, but interpolated material from other authors freely. For the period between 1100 and 1147, Robert relied upon Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum, though Robert altered the text of the Historia substantially in places. From 1147 Robert's Chronicle becomes original. Robert seems to have created an initial draft that ended in 1150, but gradually expanded the Chronicle to cover events through 1186, the year of Robert's death. The Chronicle owes much to annalistic writing in terms of style, and tends to offer few authorial judgments of the events described. Robert does, however, offer occasional comments about events that he witnessed in person. Throughout the sections original to Robert, he pays particular attention to local Church affairs, such as the succession of Norman abbots and bishops. Importance for the study of Angevin History The Chronicle is distinct as a work begun at the very start of Henry II's reign, written in a style which had become old-fashioned by the end of Henry's reign (in contrast to the forms of history-writing pioneered by secular clerics at Henry's court). Robert's Chronicle, unlike many histories from the Angevin period, was completed before the death of Henry II, the events of the Third Crusade, and the Loss of Normandy, so it does not look forward to these events as later histories often do. Though the Chronicle has received less scholarly attention than other works of the Angevin period, Robert's status as a powerful abbot has led to scholarly discussion of his relationship with Henry II, and of how history-writing figured into that relationship. Scholars such as Elisabeth van Houts see in Robert an opportunistic author, who was able to use history-writing to gain promotion and concessions from Henry II by praising Matilda's faction in his passages on the Anarchy, extolling the genealogy of the dukes of the Normans, and sticking to a conventional, accessible, and inoffensive form of annalistic writing. Robert's pro-Henry II stance is evident from the fact that he seems to have presented a copy of the Chronicle to Henry. More generally, David Bates sees in Robert a devotee of "Normanitas" who suppressed material critical of the Norman people and who sought out books about Normans from far-away places such as Sicily. Equally important for Bates, Robert displays an intense interest in the history of England, suggesting that Robert felt a sense of unified cross-Channel identity. Finally, as the scholarly debates over the date at which Robert acquired Henry of Huntingdon's Historia and over Robert's scribal practices indicate, the Chronicle allows us to peak into the twelfth-century intellectual and social spheres that fostered history-writing. It is clear from Robert's incorporation of the Historia into his Chronicle and from the copies had had made of the Chronicle that there was an intense demand for history-writing during the Angevin period, and that there was a strong, self-conscious dialogue between monastic scholars of different parts of the Angevin Empire. Bibliography Bates, David. "Robert of Torigni and the Historia Anglorum." In The English and Their Legacy: 900-1200: Essays in Honour of Ann Williams, edited by David Roffe, 175-84. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012. Delisle, Léopold. "Préface," In Chronique de Robert de Torigni, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel, 2 volumes, edited by Léopold Delisle, i-lxv. Rouen: A. Le Brumentm 1872-3. Howlett, Richard. "Preface." Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II., and Richard I.: Vol. IV; The Chronicle of Robert of Torigni, Abbot of the Monastery of St. Michael-in-Peril- of-the-Sea, edited by Richard Howlett, vii-lxix. London: HMSO, 1889. Pohl, Benjamin. "Abbas qui et scriptor? The Handwriting of Robert of Torigni and His Scribal Activity As Abbot of Mont-Saint-Michel (1154-1186)." Traditio 69 (2014): 45-86. _____. "The Date and Context of Robert of Torigni’s Chronica in London, British Library, Cotton MS. Domitian A. VIII, ff. 71r-94v." Electronic British Library Journal (2016): http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2016articles/article1.html. Van Houts, Elisabeth. "Latin and French as Languages of the Past in Normandy during the Reign of Henry II: Robert of Torigny, Stephen of Rouen, and Wace." In Writers of the Reign of Henry II: Twelve Essays, edited by Ruth Kennedy and Simon Meecham-Jones, 53-78. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. _____. "Robert of Torigni As Genealogist." In Studies in Medieval History Presented to R. Allen Brown, edited by Christopher Harper-Bill, Christopher J. Holdsworth, and Janet L. Nelson, 215-34. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1989. _____. "Le roi et son historien: Henri II Plantagenêt et Robert de Torigni, abbé du Saint-Michel." Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 37, no. 145-1 (1994): 115-8. Kasey Fausak MS Stowe 62, f. 130v. Image courtesy of the British Library. Description: William of Newburgh, also known as William Parvus, was an Augustinian canon in the priory of Newburgh, born c. 1136, who is most well known for his History of English Affairs, composed in the last few years of the 12th century. This work, divided into five books, covers the history of England from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066 and cuts off abruptly in 1198. The preface indicates that the Historia was written at the request of Ernald, abbot of Rievaulx, and includes all of the common tropes of 12th century historical writing: the writer not being great enough for the task at hand, but, due to the importance of the current events of the time and the urging of his compatriots, will do his best. The text includes some classical references, but relies heavily upon religious and Biblical allusions, as to be expected with Williams’s religious background. The prologue to Book I then jumps straight into a diatribe against Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Britannica. William spends several pages completely eviscerating Geoffrey’s work, fact-checking dates, battles, and kings to prove that the tales of King Arthur must, naturally, be just tales, and that by claiming Geoffrey’s work as history Geoffrey does a great disservice to those unfortunate enough not to know any better. Once firmly establishing that his own work, by contrast, will be based only in facts, he begins Book I. Book I begins with the Norman invasions and ends with the death of King Stephen. This coincides with the year of William’s own birth, which he provides as explanation for then detailing events more fully. Book II picks up with Henry II’s accession and continues through the Young King’s revolt, ending with the reconciliation after the revolt. Book III then covers a variety of events, including the Third Crusade. Book IV commences with the coronation of Richard and ends with his return from captivity. Book V picks up immediately thereafter, but does not end with a dramatic event as the first four books do, leading some historians, including Walsh & Kennedy, to speculate that William died suddenly while writing, sometime after the events of 1198 with which Book V ends. William also composed a commentary on the Song of Songs and has at least three sermons attributed to him, but little is known about William’s personal life other than the small and rare references to himself he makes throughout his work. Importance for the Study of Angevin History: William of Newburgh’s work recounts the events of a large portion of Angevin history, but was not created for a patron at court connected to any of the royal figures under discussion. While not a completely unbiased source, William has been called the “father of historical criticism,” for his relatively even and balanced critiques. William was writing for an ecclesiastical audience, so in addition to descriptions of political events, he also covers important movements in the church, such as the election of an English pope. As with other chronicles, the History of English Affairs is helpful for studying not just the narrative history of the time period, but how those events were interpreted by contemporaries. Like a modern historian, William describes events, provides evidence for that description, and explains the long and short-term implications of those events. Willam’s coverage of the Becket affair in particular has been praised by historians. Despite the title, William also covers affairs outside of England that have an impact on the English, leaving his work a source as fodder on either side of the “empire” debate. William’s references to historians such as Gildas, Bede, and Geoffrey of Monmouth, other works completed “in our own time,” and use of sources such as Henry of Huntingdon lends itself to the study of sources for the study of the Angevin empire in a meta-type analysis. Finally, it appears as if William spent his entire life in religious communities in Yorkshire. Perhaps most striking about this work is that, despite his stationary geographic location, he had enough knowledge of outside affairs to compose such a thorough Historia. Manuscripts:

Editions: William of Newburgh, The History of English Affairs: Book I. Edited and translated by P. G. Walsh and M. J. Kennedy. Oxford: Aris & Phillips, 1988. William of Newburgh, The History of English Affairs, Book 2. Edited and translated by P.G. Walsh and M.J. Kennedy. Oxford: Aris & Phillips, 2007. William of Newburgh, Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I. Edited by Richard Howlett. London: Longman & Co, 1884-9. The Church Historians of England, volume IV, part II. Translated by Joseph Stevenson. London: Seeley's, 1861. (This edition is what Scott McLetchie used in 1999 to publish on Fordham’s own Medieval Sourcebook.) William of Newburgh, Historia rerum Anglicarum. Edited by H.C Hamilton. London: English Historical Society, 1856. William of Newburgh, Rerum Britannicarum medii aevi scriptores. Edited by Thomas Hearne. Oxford, 1719. William of Newburgh, Historia rerum Anglicarum. Edited by John Picard, Paris, 1610. William of Newburgh, Historia rerum Anglicarum. Edited by William Silvius. Antwerp, 1567. Bibliography:

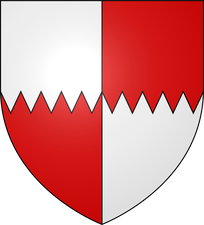

Marco Damiano Arms of FitzWarin Manuscript

British Library, Royal 12.C.XII, ff. 33-60v Editions and Translations Brandin, Louis. Fouke Fitz Warin; Roman Du XIVe Siècle, Édité. Les Classimques Français Du Moyen Âge: [63]. Paris, H. Champion, 1930 Burgess, Glyn S. trans. Two Medieval Outlaws: Eustace the Monk and Fouke Fitz Waryn. Woodbridge, Suffolk ; Rochester, NY : D.S. Brewer, 2009. Hathaway, E. J., P. T. Ricketts, C. A. Robson, and A. D. Wilshere, eds. Fouke Le Fitz Waryn. Anglo-Norman Text Society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1975. Stevenson, Joseph, ed. and trans. The Legend of Fulk Fitz-Warin. In Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores, or Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages. Rolls Series. Vol. 66. London: Longman and Co., 1857, 1875; rpt. Kraus Reprint, 1965. Pp. 275-415. Wright, Thomas, ed. and trans. The History of Fulk Fitz Warine, An Outlawed Baron in the Reign of King John. London: The Warton Club, 1855. Description Fouke le Fitz Waryn is an Anglo-Norman romance centering on the life and deeds, as well as family history, of Fulk III. The historic Fulk was a Marcher baron and lord of Whittington, in Shropshire, who in 1200 A.D. rebelled against King John over the succession to the castle thereof. After years of living as an outlaw and bandit, Fulk and his followers were reconciled to the king and he was restored to his rightful inheritance in 1204 A.D. The prose romance, adapted from a lost late-thirteenth century verse source by an unknown author, is a loose and fanciful adaptation of the baron's exploits, detailing his adventures throughout England and the mythic roots of his lineage in the style and genre of what has been termed a "dynastic romance." Importance for the study of Angevin History Given the figure of King John himself as the villain of the story and personal enemy of the tale's eponymous hero, the romance of Fouke le Fitz Waryn deals intimately with how the legacy of the Angevins was passed down and interpreted in English cultural memory. Moreover, as is true of dynastic romances in general, it shows a curious mix detailed factual knowledge, embellishment, and outright fantasy in the events and places it describes. The author is keenly interested in and demonstrates an awareness of local geography and topography, as well as history dating back to the time of the Conquest. In seeking for its central character and his family an origin justifying their claims to nobility, the tale reaches back not only to the time of William, but entrenches itself in a framework of native English and Welsh history drawn from authorities such as Geoffrey of Monmouth. This interest in intensely local settings and concerns for its subjects sets the dynastic romance apart from its more Continental, standard progenitor. Oftentimes the stories claim for their respective heroic lineages descent from Anglo-Saxon, rather than Norman, roots entirely. As such, Fouke le Fitz Waryn can be seen as a product of and for an aristocracy that was increasingly moving away from its "French" heritage in pursuit of a more insular identity. Bibliography Crofts, Thomas H. and Rouse, Robert. “Middle English popular romance and national identity.” In A Companion to Medieval Popular Romance, Edited by Radulescu, Raluca and Rushton, Cory James. Studies in Medieval Romance, 79-95. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2009. Francis, E. A. "The Background to Fulk Fitzwarin." In Studies in Medieval French Presented to Alfred Ewert in Honour of his Seventieth Birthday. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961. Pp. 322-27. Hanna, Ralph. "The Matter of Fulk: Romance and History in the Marches." The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, no. 3: 337. Weiss, Judith. ““History” in Anglo-Norman romance: the presentation of the pre-Conquest past.” In The Long Twelfth-Century View of the Anglo-Saxon Past, Edited by Brett, Martin and Woodman, David A.. Studies in Early Medieval Britain and Ireland, 275-287. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015. Alexandra Ponti Manuscripts

Editions and Translations

Description Thomas of Monmouth’s Life retells the birth, death, and subsequent miracles of thirteen-year-old William of Norwich who was believed to have been killed in a ritual murder performed by Jews in celebration of the Jewish holiday of Passover. Monmouth began his seven-volume hagiography of the tanner’s apprentice six years after the teen’s death in 1144, creating a new saint cult popular in and around Norwich for several hundred years. Little is known about Thomas of Monmouth other than he was a Benedictine Monk at Norwich Cathedral Priory in the mid-twelfth century. Importance for the Study of Angevin History Since its first published edition, historians have long-doubted the credibility of Monmouth’s Life, and most agree it is a myth. However, Monmouth does accurately depict the growing hostility with which Christians looked upon Jews in the twelfth century, and it is supposed to be the first use of the blood libel, the ritualistic killing of Christians by Jews. This started a system of belief that any suspicious death of a Christian child was thought to have been murdered by Jews, and no Christian child was considered safe in the hands of a Jew. Bibliography

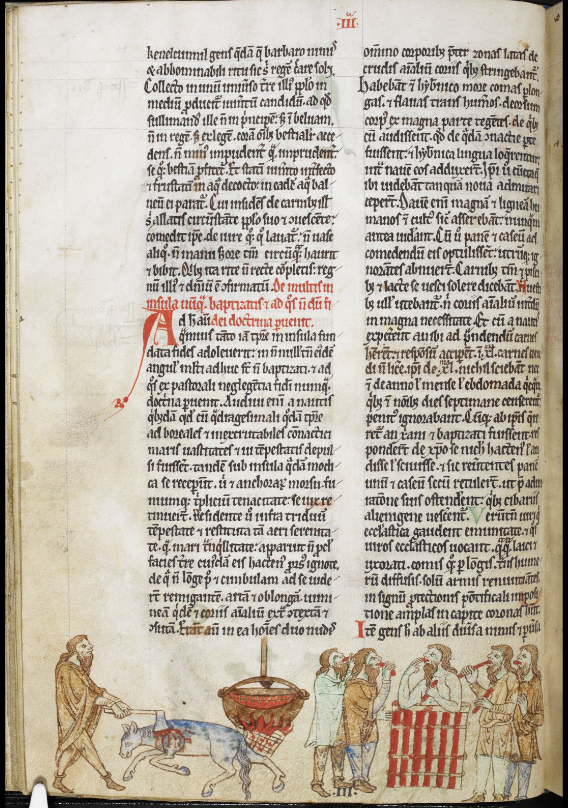

Tanner Smoot Royal MS 13 B. VIII, f.28v Description:

The Topographia Hibernica represents the first of the major literary works written by Gerald of Wales. Born at the castle of Manorbier in Pembrokeshire around 1146 A.D., Gerald pursued a religious career from an early age. After years of study in Paris, Gerald returned to Britain where fulfilled various roles throughout his long career, such as archdeacon of Brecon, administer of the see of St. David, ecclesiastic counsellor, and royal tutor. Several members of Gerald's family (de Barri) took part in the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169 A.D. and Gerald first visited Ireland in 1183 A.D. to assist and counsel his brother and uncle. Gerald began writing the Topographia during his second trip to Ireland in 1185 A.D. as the royally appointed tutor of Prince John, and completed the work after three years. Although Gerald presented a completed version of his work to Archbishop Baldwin in 1188 A.D., he revised the work no less than three times during the course of his life. The fourth and final revision, completed shortly before his death in 1223 A.D., proved twice as long as the original work. Dedicating his first edition of the Topographia to King Henry II of England, Gerald sought to describe the land and people of Ireland. Gerald divides the book into three sections detailing the island's geography, wonders, and inhabitants respectively, and claimed to have used no external source for the first two sections. The content of the Topographia generally describes Ireland as a fertile land inhabited by a barbarous, unfaithful, semi-pagan people. The fabulous nature of many of the anecdotes and tales has led several of the first modern commentators of Gerald to discount his usefulness as a historian and note his apparent credulity. Nevertheless, Gerald's Topographia Hibernica, much like Adam of Bremen and Helmold of Bosau's respective histories of the Danes and Slavs, served to justify the Anglo-Norman conquest and colonization of Ireland by allowing the invaders to assume a moral position in their engagement with the native population. Despite the limited nature of Gerald's travels and his overt bias towards the Irish, Gerald's Topographia Hibernica and Expugnatio Hibernica constitute two of the major extant sources of twelfth-century Ireland. Gerald's Topographia additionally utilized a method of comparative social inquiry and introduced concepts of social evolution which proved influential to subsequent medieval historians. Importance for the Study of Angevin History: The first of Gerald's modern editors criticized him as an unreliable, vain, and credulous historian whose work in no substantial way accurately describes twelfth-century Irish society. Yet, as an individual politically connected to the English royal court and related to the high nobility of the Welsh Marches and Anglo-Irish territories, Gerald's works provide unique insight into the opinions and goals of the contemporary Anglo-Norman lords. Although Gerald's characterizations do not represent an attempted objective insight into contemporary Irish society, his distinctions nevertheless suggest implicit differences between the cultures of the Anglo-Normans and the Irish. Gerald's choices concerning the type of stories to tell and what comparisons to make inform on the social concerns, expectations, and civil assumptions of Gerald's peers. Manuscripts: Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, 400 [B] Cambridge, University Library, Mm. 5. 30. Douai, Bibliotheque municipal, 887 Dublin, National Library of Ireland, MS 700 London, British Library, Additional 33991 London, British Library, Additional 34762 London, British Library, Additional 44922 London, British Library, Arundel 14 London, British Library, Royal 13 B. viii London, Westminster Abbey, 23 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rawlinson B. 188 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rawlinson B. 483 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France, latin 4846 Editions: Gerald of Wales. The History and Topography of Ireland. Translated by John F. O'Meara. London: Penguin Group, 1982. Giraldi Cambrensis: Opera Vol. V. Edited by James F. Dimock. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1867. Bibliography: Bartlett, Robert. Gerald of Wales: 1146-1223. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982. Dimock, James F. Preface to Giraldi Cambrensis: Opera Vol. V, ix-lxxxix. By Gerald of Wales, edited by James F. Dimock. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1867. O'Meara, John F. Introduction to The History and Topography of Ireland, 11-18. By Gerald of Wales, translated by John F. O'Meara. London: Penguin Group, 1982. Rooney, Catherine. "The Early Manuscripts of Gerald of Wales." In Gerald of Wales: New Perspectives on a Medieval Writer and Critic, edited by Georgia Henley and A. Joseph McMullen, 97-110. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018. Further Reading: Brown, Michelle P. "Gerald of Wales and the 'Topography of Ireland': Authorial Agendas in Word and Image." Journal of Irish Studies 20, (2005): 52-63. Sargent, Amelia Borrego. "Gerald of Wales's Topographia Hibernica: Dates, Versions, Readers." Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies 43, no. 1 (2012):241-262. Staunton, Michael. The Historians of Angevin England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. by Taylor Dickinson Genealogy of the kings of England to Edward I. Bodleian Library MS Bodl. Rolls 3, Folio: row 29, medallion 5 Manuscripts:

The surviving returns can be found in the Red Book of the Exchequer, The National Archives (UK), E164/2 For more information about the survival of manuscripts see pages 13-14 of: Vincent, Nicholas. "Introduction: Henry II and the Historians." In Henry II: New Interpretations New Interpretations, edited by Nicholas Vincent and Christopher Harper-Bill, 1-23. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2007. Editions: Navel, Henri. “L'enquête de 1133 sur les Fiefs de l'Évêché de Bayeux” Bulletin de la Societe des Antiquaires de Normandie, 42 (1934), 5-80. Description: The Bayeux Inquest of 1133 was ordered by King Henry I in order to establish what service was owed to the duke, along with what was owed to the bishop by his knights and vavassors. The inquest was managed by twelve chosen men. The returns show that one knight in every ten was owed by the bishop, Odo, to the duke for service to the king of France and one in five were owed to the duke himself, ten and twenty knights respectively. Besides the distribution of ordinary feudal service, the returns show services of castle guard, as well as aids and relief owed to the bishop within the demesne and the fiefs. Importance for the Study of Angevin History: This inquest specifically sought to determine the extent of the bishop’s rights and possessions in 1050-1097, when the office was held by Bishop Odo. Henry I’s stake in the possessions was rooted in the profits that would fall unto him during the two-year vacancy before his nominee could be consecrated. He also remained in Normandy during this period. The inquest was, at its most basic, a fiscal investigation to see which sources of revenue belonging to the bishop could be appropriated by the duke. While it contains the earliest mentions of forty days’ service, as well as the distinction between equipment and plain arms, the 1133 inquest survived because Geoffrey used the returns as a formula for conducting his own inquests into the bishop’s fiefs later on. Bibliography: Harper-Bill, Christopher, and Nicholas Vincent, eds. Henry II: New Interpretations. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2007. Haskins, Charles Homer. Norman Institutions. Vol. XXIV. Harvard Historical Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1918. Keefe, Thomas K. Feudal Assessments and the Political Community under Henry II and His Sons. Los Angeles:University of California Press, 1983. by Taylor Dickinson Description John of Salisbury’s Policraticus, meaning ‘the statesman’ in pseudo-Greek, is commonly attributed to being the first work of political theory written in the Middle Ages. There are eight books in this approximately 250,000-word compilation. The modern arrangement of the text does not reflect the order of its composition. Written from 1156-1159, John began Policraticus as a guide to demonstrate the basis of life as a good man and bring to light the false joy of his contemporaries. Being that he wrote books VII and VIII while exiled from Henry II’s court, most scholars describe this portion as ‘self-consolatory’. The work soon transformed into advice to clerical bureaucrats about how to avoid the pitfalls of life at royal and ecclesiastical courts. Books IV-VI focus on a theory of government and society which would better shelter the spiritual and physical wellbeing of civil servants, princes and their subjects. Policraticus affirms that men are morally bound to seek their own temporal fulfillment through the acquisition of knowledge and practice of virtue, much in line with the author’s background. Of political theory, John believes that the political system should be guided by the principles of nature, but men must cooperate with nature by means of experience and practice because nature does not determine human behavior. John uses narratives or stories to exemplify a lesson or doctrine, called exempla. His sources include his personal experiences at papal and royal courts. Having been a close friend of Thomas Becket and Pope Adrian IV, it is no surprise that he relays personal stories and sayings of the two within the work. Policraticus embraces references to Holy scripture, having an obvious preference for the old testament, but is also is well-known for acknowledging doctrines of pagan antiquity. John uses narratives from Christian writers such as St. Augustine and St. Jerome, along with invoking the works of classical authors like Virgil, Horace, Lucan, and Ovid. One of John’s most important sources was Aristotle’s Organon, from which infuses the doctrine of the golden mean, emphasizing moderation of character and actions, as well as the psychology of moral character into Policraticus. The treatises were not yet well-dispersed during John’s time and it is speculated that he, being one of the best-read men of the 12th century, might have been the first in the Middle Ages to read it in its entirety. Importance for the Study of Angevin History John of Salisbury, author of Policraticus, lived from 1115-1180. After studying at Mont-Saint-Geneviève, he joined the household of Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury, putting him in close proximity to major players of the Angevin Empire. This included Thomas Becket, to whom he would dedicate Policraticus and address directly throughout the text. John supported Henry II against Stephen during the turmoil but was vocal about his opposition to Henry’s policies concerning the English Church to the point where he was banished from the royal court in 1156-1157, when he would begin to compose Policraticus. He would again spend time in exile, in France or at the Papal court, during the 1160’s, when he threw his support towards Becket against Henry II and the bishops in support of the king. Despite his animosity towards the crown, John found himself distanced from Thomas Becket’s unwillingness to compromise with Henry. In Policraticus, he writes that secular government should be permitted to be conducted without direct interference by the Church. He also addresses the role of ‘tyrant’ as any person with ambitions to restrict the freedom of another while also holding the power to do so, but does not limit the position to those of public officials. John tackled the ideas of private and ecclesiastical tyranny, as well. John of Salisbury was a man navigating the realms of temporal and clerical power, which is clearly displayed in Policraticus when he spends equal time criticizing the behaviors of clerics and priests as he does secular leaders. He finished this work before the assassination of Thomas Becket, thus having already put in writing his belief that the clergy were faced with a greater temptation to abuse their power and become ecclesiastical tyrants than the other two sects. John of Salisbury returned to England after Becket’s death and was appointed bishop of Chartres, where he remained until his death. Manuscripts Corpus Christi College, MS 046 British Library, Royal 13 D IV British Library, Royal 12 F VIII (Addressed to Thomas Becket) (IMAGE: Royal 12 F VIII f. 62) Bodleian Library, MS. Barlow 48 Bodleian Library, MS. Barlow 6 Bodleian Library, MS. Auct. F. 1. 8 Bodleian Library, MS. Lat. misc. c. 16 Editions and Translations John of Salisbury. Policraticus, Of the Frivolities of Courtiers and the Footprints of Philosophers. Edited by Cary J. Nederman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. Pike, Joseph B., trans. Frivolities of Courtiers and Footprints of Philosophers: Being a Translation of the First, Second, and Third Books and Selections from the Seventh and Eighth Books of the Policraticus of John of Salisbury. New York: Octagon Books, 1972. Description John of Salisbury’s Policraticus, meaning ‘the statesman’ in pseudo-Greek, is commonly attributed to being the first work of political theory written in the Middle Ages. There are eight books in this approximately 250,000-word compilation. The modern arrangement of the text Bibliography

Bollermann, Karen and Nederman, Cary, "John of Salisbury", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL= <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2016/entries/john-salisbury/>. John of Salisbury. Policraticus, Of the Frivolities of Courtiers and the Footprints of Philosophers. Edited by Cary J. Nederman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. Nederman, Cary J. John of Salisbury. Vol. 228. Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies. Tempe, AR: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2005. Nederman, Cary J. John of Salisbury. Vol. 228. Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies. Tempe, AR: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2005. Nederman, Cary J. Lineages of European Political Thought: Explorations along the Medieval/Modern Divide from John of Salisbury to Hegel. Washington D.C.:The Catholic University of America Press, 2009. Patrick C. DeBrosse London, British Library, Cotton MS Julius B XIII, fol. 48r. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=cotton_ms_julius_b_xiii_f048r Manuscripts:

(Unique) London, British Library, Cotton MS Julius B XIII, fos. 48-173. This manuscript binds together two originally-separate manuscripts, one of which contains the text of De principis instructione, and the other of which contains the so-called "Melrose Codex." The original preface of De principis instructione survives separately in Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R. 7. 11, fos. 86-92. For further information, see Robert Bartlett, "Introduction," in Gerald of Wales. Instruction for a Ruler (De Principis Instructione), ed. and trans. Robert Bartlett (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2018), xi-xiii. Editions and Translations: Gerald of Wales. Instruction for a Ruler (De Principis Instructione). Edited and translated by Robert Bartlett. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2018. [facing-page Latin and English] _____. Giraldi Cambrensis Opera, Vol. VIII: De principis instructione liber. Edited by George F. Warner. RS. London: HMSO, 1891. [Latin] _____. Concerning the Instruction of Princes. Translated by Joseph Stevenson. Felinfach: Llanerch, 1991. [reprint of 1858 ed.; partial English translation] _____. De instructione principum: Libri III. Edited by J. S. Brewer. London: Impensis societatis, 1846. [partial Latin edition] Description: Gerald of Wales, an accomplished scholar, prolific writer, and ambitious cleric, composed De principis instructione after leaving his service at the court of Henry II. He probably composed the work c.1190, but the date of the composition is difficult to reconstruct, especially since it seems that Gerald circulated Book 1 in the early 1190s, years before circulating Books 2 and 3, c.1216-7 (for the composition, see Bartlett, "Introduction," xiii-xix). Gerald left the court bitter and disillusioned: in the preface to De principis instructione Gerald denounces the court, claims that the Angevins lured him to their service with false promises (an allusion to his failure to secure the see of St. David's), complains of the discrimination he faced as a man of Welsh descent, and expresses his preference for the scholarly life to which he had returned. Throughout the body of De principis instructione, Gerald devotes himself largely to critiques of his former master, Henry II. Book 1 is a "mirror for princes," i.e. a treatise intended to model good behavior for princes, aristocrats, and high-ranking prelates. Most of the sections in Book 1 focus upon the virtues that princes must develop in order to become just and successful rulers. Gerald illustrates these virtues with anecdotes drawn from the Bible, the ancients, and his own experiences at court. Book 2 shifts into a narrative of the major events of the reign of Henry II. The narrative is polemic, dwells upon Henry's misdeeds and character deficiencies, and arcs to show Henry's fall from the heights of power. Book 2 concludes with Henry's refusal of the offer of the crown of Jerusalem, an act of impiety, in Gerald's estimation, and the beginning of his downfall. Book 3 picks up the story to narrate Henry's final years, during which Philip II of France and Henry's own sons conspired against him. Gerald follows his description of Henry's ignominious death with criticism of Richard I. Gerald closes by lamenting the failure of Prince Louis's 1216 invasion of England. Importance for the study of Angevin history: De principis instructione is the product of one of the best-connected, best-informed courtiers of the Angevin period. Gerald worked for the court directly, knew many of the most important figures of the period personally, corresponded widely, and had access to court documents. Gerald made good use of those resources, and offers us many details about the Angevin period in De principis instructione that are totally unique - either details about the events of particular years or about general court practices. Consequently, historians of the Angevin period have mined the work for a variety of purposes. De principis instructione is particularly valuable for Gerald's critiques of the Angevins, his anecdotal stories about events he witnessed at court, and his discussion of the Picts and the Welsh (which allows us to see Anglo-Norman attitudes towards people from the "Celtic fringe"). More than anything, however, it is Gerald's personal reflections on his life and career that gives us the best insights into the Angevin period. In Gerald we see a cleric who attempted - and failed - to use the court as a stepping stone to episcopal promotion. The court's appeal and its ability to attract talent becomes clear through Gerald's story. Gerald's perspective shows us, moreover, how the political was the personal in this period, as he blamed his failure to achieve office on personal jealousy and bullying, and the kingdom's crises on the king's personality. Finally, in Gerald's career we see how the intellectuals of Western Europe used rhetoric (developed in the new schools) to seek advancement or (in the case of De principis instructione) revenge through the power of writing. Bibliography: Gerald of Wales. Instruction for a Ruler (De Principis Instructione). Edited and translated by Robert Bartlett. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2018. Further Reading Bejczy, István P. "Gerald of Wales on the cardinal virtues: a reappraisal of De principis instructione." Medium AEvum 75, no. 2 (2006): 191-201. Lachaud, F. "Le Liber de principis instructione de Giraud de Barry," in Le prince au miroir de la littérature politique de l'Antiquité aux Lumières, edited by F. Lachaud and L. Scordia, 113-42. Mont-Saint-Aignan: Publications des universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2007. Petrovskaia, Natalia I. "East and West in De principis instructione of Giraldus Cambrensis." Quaestio Insularis 10 (2010): 45-59. Michael Weldon

Description: Located at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou, the royal tombs of King Henry II, Eleanor of Aquitaine, King Richard I, and Isabelle of Angoulême lie in the western bay of the abbey church’s nave. An unusual phenomenon in northern Europe, the tombs are among the first fully-sculptural, life-sized effigies. The effigies of Henry, Richard and Eleanor are of a painted tuffeau, a chalky limestone; Isabelle’s is carved of wood. While the effigies of Henry, Richard, and Isabelle depict the individuals in death, Eleanor is portrayed in the perpetual study of a devotional book. The tombs are dated circa 1199-1254 CE. Importance for the Study of Angevin History: In the tradition of queens controlling burial sites and monuments, Eleanor of Aquitaine commissioned her family tombs at Fontevraud, a place to which she had ancestral ties. Historically an elusive figure, it is suggested that through a lifetime of travel Eleanor became knowledgeable of the existing traditions of Christian dynastic burial sites and of figural funerary monuments. With the death of Henry II in 1189, Eleanor’s choice of Fontevraud as his final resting place has been interpreted as a reflection of her own political identity where her ties to the nuns would lead to the eventual repose of the souls of her family as well as her own. Bibliography: Nolan, Kathleen. “The Queen’s Choice: Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Tombs at Fontevraud,” Eleanor of Aquitaine: Lord and Lady (New York: Palgrave, 2003), 377-405. Simmons, Lorraine N. “The Abbey Church at Fontevraud in the Later Twelfth Century: Anxiety, Authority and Architecture in the Female Spiritual Life.” Gesta, Vol. 31, No. 2, Monastic Architecture for Women (1992), 99-107. Michael Weldon Manuscripts: National Library of Ireland, MS 700 Editions: Camden, W., Anglica, Hibernica, Normannica, Cambrica a veteribus scripta…ex bibliotheca Guillelmi Camden…Francofurti 1602; 2nd ed. ibid. 1603 Dimock, J. F., Giraldi Cambrensis opera, 8 vols, vol. 5: Topographia Hibernica et Expugnatio Hibernica, London, 1867 Expugnatio Hibernica: the Conquest of Ireland by Giraldus Cambrensis, ed. and tr. A.B. Scott and F.X. Martin (Dublin, 2002) Giraldi Cambrensis opera, in Rerum Britainnicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores, 8 vols, London 1861-91 O’Meara, John J., Giraldus Cambrensis in Topographia Hiberniae. Text of the first recension, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 52, section C (1948-50) 113-178. Translations: Expugnatio Hibernica: the Conquest of Ireland by Giraldus Cambrensis, ed. and tr. A.B. Scott and F.X. Martin (Dublin, 2002) Forester, T., The Historical works of Giraldus Cambrensis. Containing the Topography of Ireland, and the History if the Conquest of Ireland, tr. By Thomas Forester. The Itinerary through Wales and the Description of Wales, tr. By Sir Richard Colt Hoare. Revised and ed. T. Wright, London 1863 (Bohn’s antiquarian library). Holinshed, R., The first and second volumes of chronicles…Now newly augmented and continued…to the year 1586 by John Hooker alias Vowell gent. and others…, London 1587. The second volume contains Hooker’s translation of the Expugnatio. Description: Completed in 1189, Expugnatio Hibernica is Giraldus Cambrensis’ (Gerald of Wales) second work on Ireland. Written in Latin, Book I comprises forty-five chapters while Book II contains thirty-seven. A detailed account of the Normans coming to Ireland and their claim to its conquest, the concluding two chapters present strategies for the entire subjugation of the Irish nation and recommendations for how the Irish people ought to be governed. Importance for the Study of Angevin History: Having accompanied Henry II’s son, John, on a military expedition, Gerald of Wales in his second work on Ireland reminds the reader of ‘the five-fold right’ of the English king over the nation. By citing Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Brittaniae, placing Irish origins in the province of Gascony, and recalling that the kings of Ireland paid tribute to Arthur, it is through the mythic lens which Gerald of Wales writes that Henry II’s invasion and conquest of Ireland is justified. Bibliography: Davies, J. C., ‘Giraldus Cambrensis 1146-1946’, in Archaeologia Cambrensis 99 (1946-47), pp. 85-108; 256-280. Lydon, J. F., The Lordship of Ireland in the Middle Ages, Dublin 1972. Martin, F. X., ‘Gerald of Wales, Norman Reporter on Ireland’, in Studies 58 (1969), pp 279-92. -----, ‘The first Normans in Munster’, in Cork Hist. Arch. Soc. Jn. 76 (1971), pp. 48-71. Richardson, H. G. and Sayles, G. O., The Administration of Ireland, 1172-1377 (Irish Historical Manuscripts Commission), Dublin 1963. Ryan, M. T., The historical value of Giraldus Cambrensis’ Expugnation Hibernica (typewritten M. A. thesis submitted to University College, Dublin, 1967. Sheehy, M. P., ‘The Bill Laudabiliter: a problem in medieval diplomatique and history’, in Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society 29 (1961), pp. 45-70. |